Introduction:

At this point in their evolution Havanese appear to be a very healthy breed with an average lifespan that remains relatively long. This can best be seen from the four major health surveys conducted by the Havanese Club of America [see our section on Health Surveys]. While the parent populations of these surveys was a voluntary one- not selected in a formal or otherwise unbiased fashion - the surveys do span almost 3000 dogs from both breeders and pet owners. There appears to be no single life-threatening disease of clear genetic origin that is prevalent throughout the breed at this time.

Within small breeds as a whole however, there are clearly some health issues that are more commonly observed. The frequency and severity are often breed specific. For example, specific kinds of cardiac diseases are seen in a very large percentage of the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel population (and other forms in certain large breeds). These appear at a young age and are attributed conclusively to a genetic origin. Another example is liver disease which is frequently seen in Norfolk and Yorkshire Terriers, Shih-tzus and Maltese populations, but very very rarely in any large breeds. Some forms of liver disease are also believed to be genetic in origin. Depending on the nature of the genetic mutation, and its transmittance, it may be hard or impossible to breed away from with the tools we have at hand. And, as with any genetic pre-selection, one must be wary of its impact on other beneficial traits.

In this section we address some of the diseases and health issues that are seen in smaller breed dogs. Not all are life threatening, but may impact the quality of life of your pet. At the end of each section we provide a set of references that may be useful.

I. Liver Disease

Blood carried to the liver arrives largely via the portal vein, which drains the intestines, stomach, pancreas, and spleen. This blood is rich in nutrients that have been extracted from food. Within the liver, the portal vein branches into smaller and smaller vessels allowing the blood to spread throughout the organ to the individual liver cells, whose functions are:

-

filtering out toxins in the blood

-

manufacturing or storing sugar for energy

-

processing drugs and other chemicals

-

making proteins

Portosystemic Vascular Anomalies (PSVA or “liver shunts”) and Hepatoportal Microvascular Dysplasia (MVD) are two common forms of liver disease. PSVA occurs when portal blood is diverted around the liver (shunted), while MVD occurs when blood is diverted from the microscopic vessels within the liver. These vessels can be underdeveloped or absent, positioned abnormally and/or throttled or there may be microscopic lesions on the liver. The result of either case is a liver that does not perform its normal functions efficiently. Clinical signs result because the dog cannot clear out toxins, add, remove or process drugs, and/or he lacks the building blocks for growth and repair. Clinical signs may also result from a buildup of toxins such as ammonia, which predispose the dog to cognitive impairment, urinary tract inflammation and infection.

Both PSVA and MVD are diseases of genetic origin. They are believed to be related and are seen almost exclusively in small-breeds such as Yorkshire terriers, Maltese, Cairn terriers, Tibetan spaniels, Shih-tzus, Havanese, and others. The two health surveys conducted by the HCA suggest that the incidence in Havanese is relatively small.

The mode of inheritance is most consistent with “autosomal dominance with incomplete penetrance.” This means that it is not associated with the sex chromosomes, but simply determined by a single gene that one parent can pass to an offspring, the result having varying degrees of severity. Like many heritable diseases, breeding away is generally not effective, in part because of the difficulty to reliably detect/diagnose all carriers.

MVD and PSVA are often first detected in young dogs with no symptoms, by four to six months of age, but as early as six weeks- frequently during an otherwise routine examination where blood work indicates elevated liver enzymes. As indicated for example in Dr. Sharon Center’s article below, diagnosis is difficult and sometimes inconsistent in part because of the variation in severity that may exist. Often, the total serum bile acid (TSBA) test is done before and after eating, but it cannot distinguish between MVD and PSVA. A Protein-C test can be used to help distinguish between the two conditions. Other diagnostic tools are available including for example biopsies and 3D – CT imaging.

A more detailed description of liver disease and treatment can be found in the references below:

General Discussion: https://www.merckvetmanual.com/digestive-system/hepatic-disease-in-small-animals/portosystemic-vascular-malformations-in-small-animals

For more information on liver disease click on following links:

PSVA and MVD in Maltese http://www.americanmaltese.org/ama-health-information/portosystemic-vascular-anomalies-psva-and-microvascular-dysplasia-mvd

MVD: http://www.petmd.com/dog/conditions/genetic/c_dg_hepatoportal_microvascular_dysplasi

Dr. Sharon Center: https://www.acvs.org/files/proceedings/2011/data/papers/096.pdf

Dr. Karen Tobias: https://works.bepress.com/karen_tobias/21/

II. Kidney Disease

Residing in the upper abdominal cavity, the Kidneys are two bean-shaped organs of the urinary system. Their primary functions include:

-

Waste excretion: Filtering out toxins, excess salts, and urea, a nitrogen-based waste created by cell metabolism.

-

Balancing of water levels: through the chemical breakdown of urine, the kidneys react to changes in the body’s water level throughout the day, adjusting the level to leave water in the body instead of excreting it.

-

Regulating blood pressure: Kidneys need constant fluid pressure to filter the blood. When it drops too low, the kidneys increase the pressure by producing a blood vessel-constricting protein (angiotensin). This also signals the body to retain sodium and water.

-

Regulating red blood cell count: If the kidneys do not get enough oxygen, they excrete erythropoietin, a hormone that stimulates the bone marrow to produce more oxygen-carrying red blood cells.

-

Regulation of PH: The kidneys help balance the acids that are produced by cellular metabolization. Foods that are consumed can either increase or neutralize the acid in the body.

Congenital and developmental kidney diseases are those in which the kidney may be abnormal in appearance, function, or both. These diseases may result from inherited or genetic problems or disease processes that affect the development and growth of the kidney before or shortly after birth. Non-hereditary causes may include infectious agents, Canine herpes virus, response to medications, and dietary factors. Most dogs are diagnosed before five years of age.

Nephrolithiasis is the condition in which clusters of crystals or stones -- known as nephroliths or “kidney stones” -- develop in the kidneys or urinary tract. There are a number of causes and risk factors that may contribute to their development; eg: the oversaturation of stone-forming materials in the dog's urine or increased levels of calcium in the urine and blood, and diets that produce high pH (alkaline) urine, and recurrent urinary tract infections. Some breeds of dogs appear to be particularly susceptible to one form of crystal or another (eg: calcium oxalate or urate nephroliths).

The two health surveys conducted by the HCA suggest that the incidence of diseases of the kidney and the development of kidney stones in Havanese is relatively small.

For a more detailed description of congenital and developmental kidney diseases, kidney stones, and renal failure, see for example:

http://www.petmd.com/dog/conditions/urinary/c_dg_congenital_developmental_renal_diseases

http://www.petmd.com/dog/conditions/urinary/c_dg_nephrolithiasis

http://www.petmd.com/dog/conditions/urinary/c_multi_renal_failure_chronic

III. Cardiac Disease

Background and Synopsis

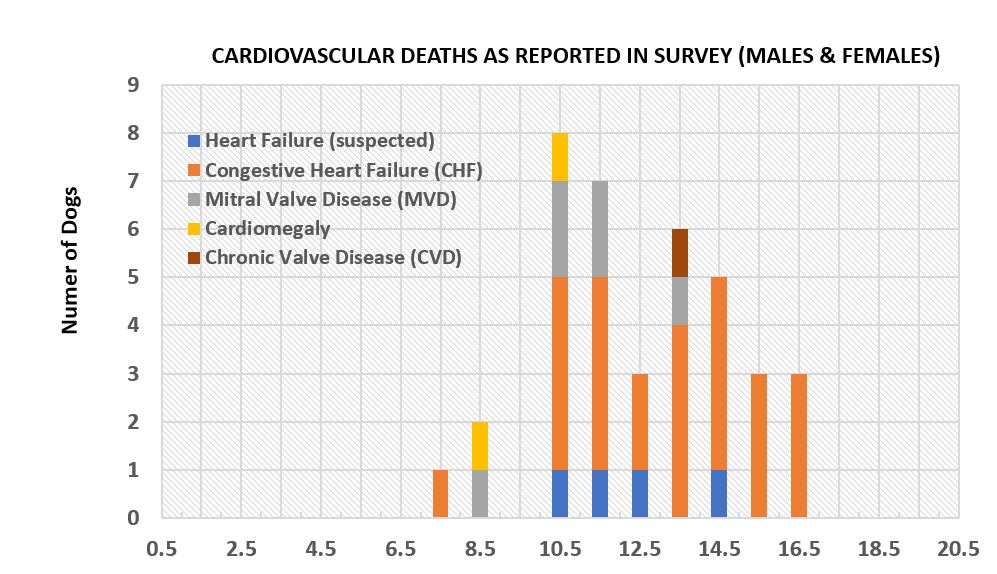

The 2018-2019 Rainbow Bridge Survey found cardiovascular disease to be one of the two most prominent health issues contributing to early death in Havanese (see Figure 1). No predominant underlying form of cardiac disease was identified in the individual survey responses - congestive heart failure being listed as the outcome in most cases. The mean age at death was 12.4 +/- 0.4 years, almost 3 years earlier than the natural lifespan exhibited in the survey population as a whole. And, while no statistical difference between male and female lifetimes was observed, the survey indicated that females were significantly more prone than males to die from a cardiovascular disease.

While cardiovascular disease is a prominent contributor to Havanese mortality, the survey suggests it to be more the result of natural aging, rather than of congenital or genetic origin, with congestive heart failure being the most frequent final outcome. Dogs dying of congestive heart failure may still live quite long lives, as can be seen in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. The frequency of diagnosed and reported cardiovascular disease by age for 38 males and females from the Rainbow Bridge Survey.

Mitral Valve Disease

Mitral valve disease (MVD) is the most common heart disease in all breeds of dogs, accounting for more than 70% of all canine cardiovascular disease. The disease manifests as a slow but progressive condition in which the mitral valve thickens, resulting in an imperfect seal between the chambers of the heart. The risk of MVD increases with age and is most common in small to medium sized dogs, developing typically after about six years of age. Often symptoms are not recognized by owners and the disease goes undetected until the dog reaches about nine years of age or older.

The first step in the diagnosis of MVD is hearing a murmur during a cardiac examination (cardiac auscultation). As dogs age, the mitral valve naturally tends to degenerate, so many older dogs will have some form of mitral valve disease. Evidence from the most susceptible canine breeds indicate a strong inherited component to the disease, with a polygenic mode of inheritance. The level of exercise, the degree of obesity, and diet are usually not attributed to causing MVD in these breeds.

MVD has four major stages:

- Stage A: Patients at risk, no symptoms (for example, Cavalier King Charles Spaniels where MVD appears as early as 5 years in ~50% of dogs, and has a genetic, heritable basis).

- Stage B1: Heart murmur heard by your veterinarian, but no heart enlargement detected on echocardiogram.

- Stage B2: Heart murmur heard by your veterinarian and heart enlargement detected on echocardiogram.

- Stage C: Symptoms of congestive heart failure (CHF) present (exhibits difficulty breathing).

- Stage D: Refractory congestive heart failure (receiving maximum doses of medications but symptoms are still present).

The American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM) recommends echocardiograms be performed whenever murmurs are heard to accurately identify the cause.

Dogs with MVD may not exhibit any noticeable symptoms for a long time. Once a murmur is even detected, it typically takes several years for there to be sufficient damage to the heart that owners begin to notice a cough caused by the enlarged heart pushing on the airways or by congestion in the lungs themselves.

An increase in the resting breathing rate is also an indicator of worsening heart disease. Most dogs have a respiratory rate at home that is less than 30 breaths per minute. If the respiratory rate starts to increase above what is normal for that dog, specifically, if it exceeds about 40 breaths per minute, this may be a sign that heart failure is starting to develop.

Other Cardiovascular Conditions

There are several other common cardiovascular conditions identified in dogs:

Dilated Cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a disease of the heart muscle which causes the heart to enlarge and become thin walled, resulting in progressive heart failure. This disease is a common inherited disease with breed specific DNA variants.

Pulmonic Stenosis (PS) is an abnormality of the pulmonary valve that limits blood flow to the lungs; left untreated dogs tend to die before five years of age.

Ventricular Arrhythmias have DNA mutations which are breed specific. These are abnormal heartbeats that begin in the lower heart chambers (causing the heart to beat too fast) and can cause sudden death, often between 12 and 24 months of age.

Sub-valvular Aortic Stenosis (SAS) is a heart defect characterized by a fibrous ridge below the aortic valve resulting in an average lifespan of about 19 months. SAS has genetic mutations which are breed specific.

Atrial Fibrillation (AF) is a common heart rhythm abnormality affecting all breeds of dogs usually coexisting with heart failure.

Tricuspid Valve Dysplasia (TVD) is a developmental anomaly of the tricuspid valve of the heart. TVD has breed specific genetic predispositions.

Congestive Heart Failure (CHF) is a condition which causes difficulty breathing because of fluid accumulation in the lungs. MVD and DCM are common causes of CHF.

Myxomatous mitral valve degeneration (MMVD) leads to structural heart changes and CHF; genetic mutations appear to be polygenetic. In Cavaliers for example diagnosis prior to five years of age is considered early onset and considered to be "highly heritable."

Cardiac Tamponade refers to compression of the heart caused by fluid collecting in the sac surrounding the heart. It prevents the ventricles from expanding properly.

Cardiomegaly refers to an enlarged heart, which is usually a sign of another condition, such as a heart valve problem or other heart disease.

Treatment

At the present time there is no cure for heart disease but therapies do exist that can delay the progression of the disease. Dogs exhibiting CHF from moderate to severe valvular insufficiency or dilated cardiomyopathy will often be started on the drug pimobendan when actual chamber enlargement is first detected. Studies show that for these dogs, the pimobendan regimen can delay the development of congestive heart failure by about 15 months on average.

Recommendations for Havanese:

Cardiac disease appears to show up mid- to late-life in Havanese. An annual auscultation by a Board Certified Veterinary Cardiologist beginning around 5 years of age will increase the likelihood of early detection and treatment that can slow the progression of disease. If a murmur is detected, typically the cardiologist will follow with an echocardiogram for a more precise diagnosis. This may be repeated at a later time to track the progression of the disease and to adjust the treatment.

While the field of canine genetics is still very new, the AKC Canine Health Foundation has several research grants studying the genetics of heart disease.

Miscellaneous References and Resources

Chronic Mitral Valve Insufficiency in Dogs: Recent Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment. Sang-II Suh, Dong-Hyun Han, Seung-Gon Lee, Yong-Wei Hung, Ran Choi and Changbaig Hyun; Published in: Canine Medicine - Recent Topics and Advanced Research, 2016, Chapter 5.

Degenerative Mitral Disease, Small Animal Hospital, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Florida;

Identifying Congenital Heart Disease, Veterinary Practice News. Kim Campbell Thornton;

See: https://www.veterinarypracticenews.com/identifying-congenital-heart-disease/

Catch Heart Disease in Dogs Early, Veterinary Medicine at Illinois. Hannah Beers;

Canine Heart Failure - Early Diagnosis, Prompt Treatment. Mark A. Oyama.

Univ. of Penna. Departmental Papers (Vet). May 2011.

Holter Monitoring in Clinically Healthy Cavalier King Charles Spaniels, Wire-Haired Dachshunds, and Cairn Terriers. C.E. Rasmussen, S. Vesterholm, T.P. Ludvigsen, J. Häggström, H.D. Pedersen, S.G. Moesgaard, L.H. Olsen. J.Vet.Int.Med. May 2011; 25(3):460–468.

Mitral Valve Disease and the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel;

See: https://cavalierhealth.org/mitral_valve_disease.htm

Myxomatous Mitral Valve Disease in Dogs: Does Size Matter? Heidi G. Parker and Paul Kilroy-Glynn. J.Vet.Card. March 2012; 14(1): 19–29.

Heart Rate, Heart Rate Variability, and Arrhythmias in Dogs with Myxomatous Mitral Valve Disease. C.E. Rasmussen, T. Falk, N.E. Zois, S.G. Moesgaard, J. Häggström, H.D. Pedersen, B. Åblad, H.Y. Nilsen, L.H. Olsen. J.Vet.Int.Med. Jan/Feb 2012;26(1):76-84.

Historical Review, Epidemiology and Natural History of Degenerative Mitral Valve Disease. Michele Borgarelli, James W. Figure 1Buchanan. J.Vet.Card. March 2012; 14:93-101.

Genome-wide Analysis of Mitral Valve Disease in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels. Anne T. French, Rob Ogden, Cathlene Eland, Gibran Hemani, Ricardo Pong-Wong, Brendan Corcoran, Kim M. Summers. Vet J; July 2012;193(1):283-286.

Whole Genome Sequencing to Explore Genetic Risk Factors in Canine Myxomatous Mitral Valve Disease. Melanie Hezzell, Marsha Wallace, Jenny Wilshaw, Stephen Hare, Nicholas Timpson, Adrian Boswood, Lucy Davison. 2020 ACVIM Forum. June 2020. J.Vet.Intern. Med. Doi: 10.1111/jvim.15903.

Management of Incidentally Detected Heart Murmurs in Dogs and Cats. Etienne Cote, DVM etal. J.Vet.Card., March 2015; 17:245-26.

American Kennel Club Canine Health Foundation Educational Resources;

See: https://www.akcchf.org/educational-resources/

IV. Dental Health in Havanese

Authors: Carol Croop and Dr. Rafe H. Schindler

INTRODUCTION

Oral disease is the No. 1 health problem diagnosed in dogs, according to the State of Pet Health 2016 Report, which collected data from 2.1 million dogs. As in humans, there may always be environmental factors, but most dental issues – both structural and propensity to disease - are believed to be of genetic origin. Toy breeds are more susceptible to dental issues than larger dogs because their jaws are small in relation to the size of their teeth. This results in overcrowding of the teeth that can lead to an incorrect bite, misalignment of individual teeth (malocclusions), and the retention of deciduous teeth (puppy teeth). Like all breeds, Havanese are also susceptible to tooth and gum diseases and decay. Fortunately, many mitigations are available to reduce the frequency and severity of problems.

STRUCTURAL ISSUES

The AKC breed standard is a written description of the ideal specimen of a breed - it identifies characteristics that become both the breeder’s “blueprint” and the ”scoresheet” used by dog-show judges to evaluate the breed. In the section describing the Head, the Havanese standard specifies that the muzzle be full and rectangular. Regarding the teeth, the standard states that a scissors bite is ideal and a full complement of incisors is preferred. Structurally, that full rectangular muzzle affords the best opportunity for the correct spacing of incisors without overcrowding. In contrast, a “snipey” muzzle (pointed and narrow) sometimes results in weak jaws, malocclusions and a poor bite.

Dr. Jan Bellows, Diplomate of the American Board of Veterinary Practitioners and past president of the American Veterinary Dental College, states that prevention of dental disease can in part be accomplished through proper breeding. He advises that it is very important to selectively breed dogs that do not have dental disease. When evaluating breeding stock it is important to look at the numbers of teeth, how and if they are crowded, and if there are too many or too few teeth. “A lot of our dental problems are inherited,” says Bellows, “and it’s very important that the mother and father of the pups are checked dentally before breeding.”

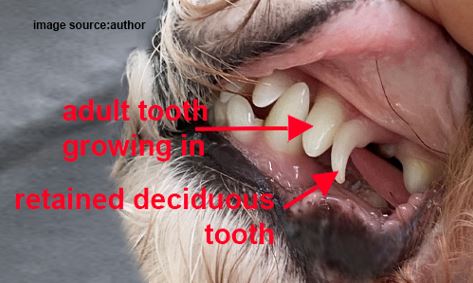

Figure 1. Retained deciduous upper canine

Retained puppy teeth are common in Havanese and may contribute to overcrowding and adult malocclusions as shown in Figure 1. They occur when the permanent tooth bud does not grow immediately beneath the deciduous (puppy) tooth, so the permanent tooth does not cause the root of the deciduous tooth to be resorbed.

When a deciduous tooth does not fall out it is referred to as a persistent tooth. When this happens, the position of the puppy tooth forces the permanent tooth to erupt in an abnormal position, possibly causing pain and damage from contact of the teeth with other teeth and soft tissue.

Dr. Bellows cautions that persistent deciduous teeth need to be extracted promptly in order to avoid these secondary problems. “In most cases, it is not recommended to wait until your pet is neutered or spayed. Extraction of the persistent tooth will require general anesthesia. Your veterinarian will take special care during the extraction to avoid damaging the developing roots of the new permanent tooth.”

PERIODONTAL DISEASE

Periodontal disease affects the structures that support the tooth. These are the periodontal ligament, which attaches the tooth to the surrounding bone, the gums around the tooth (called the gingival margin), and the bone around the tooth.

Just like with people, periodontal disease begins when plaque forms every day on the tooth surface. After a dental cleaning at the human dentist your teeth feel nice and smooth. If you go a day without brushing, a film develops over your teeth, that is plaque. If that plaque is not brushed off every day, it attracts minerals and bacteria, turning it into tartar. As plaque accumulates at the gum line, bacteria permeate into the surrounding tissue. The gums then begin to recede or pull away from the teeth, allowing more bacteria to accumulate.

Some dogs develop irreversible periodontal disease, says Professor Sandra Manfra Marretta, D.V.M., head of small animal dentistry at the University of Illinois. “In advanced disease, the periodontal ligament, which attaches the tooth to the surrounding bone, is destroyed, resulting in the eventual loss of teeth. In small-breed dogs, advanced periodontal disease may also cause the jaw to break because of

Figure 2. Visible plaque and tartar hides bacteria accumulating below the gum line (right). Same teeth when clean (left).

bone loss,” says Dr. Marretta. In Figure 2, provided by Dr. Stefanie Wong, DVM, you will see healthy teeth and gums in the picture on the left. Although there is severe plaque and tartar accumulation in the picture on the right, the biggest threat to this dog’s health cannot be seen with the naked eye.

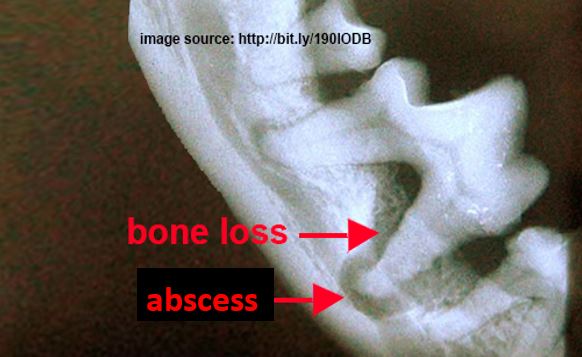

Figure 3. Bone loss and root abscess

It is the bacteria that accumulates below the gum line that destroys the supporting tissues around the tooth, leading to bone loss and root abscess (infection of the tooth root). In Figure 3 note the bone loss (white = bone) around the tooth as well as a very large root abscess (pocket of infection surrounding the root or bottom tip of the tooth).

Bacteria can easily travel to the bloodstream via the receding gums, where they are carried to other organs within the body. Dogs with severe periodontal disease have been shown to have more severe microscopic damage to their heart, kidneys and liver than their counterparts with less periodontal disease.

PREVENTATIVE HOME CARE

“The good news about periodontal disease is that it is 100% preventable as long as preventative care is started early,” says Dr. Wong. “Regular brushing (daily if you can, ideally every 3 days to prevent that plaque from turning into tartar) is the gold “standard.”

Human toothpaste and/or baking soda should never be used for dogs. Human toothpaste can cause internal problems if it is swallowed, and baking soda has a high alkaline content that can upset the digestive tract. Pet toothpastes are safe to be swallowed and come in flavors that dogs find appetizing. Also, many pet toothpastes contain enzymes that help break down plaque which reduces the time you need to spend brushing your dog's teeth.

Make tooth-brushing a positive experience by starting out slowly and praising your dog throughout the process. Start by rubbing your finger or a moistened gauze square over the outer surface of a few teeth, using a back-and-forth motion. Focus on the area where the gum meets the tooth surface, and only continue this for a few seconds before stopping and rewarding your dog. When your dog is used to you rubbing his teeth, let him taste some pet toothpaste from your finger. You can then apply a small amount to the gauze square and rub it over the teeth. Once your dog is comfortable with you rubbing his teeth, introduce a toothbrush or just continue with a gauze square moistened with clean water.

Apply a small amount of toothpaste to the toothbrush or gauze. To brush the upper teeth, gently raise your dog's lips by placing your free hand over your dog's muzzle. Use your thumb and index finger to lift the lips.

To brush the lower teeth, you will need to open your dog's mouth a little. This can be done by gently tilting your dog's head backward while holding onto his muzzle with the thumb and index finger of your free hand.

Start by concentrating on brushing the outside surfaces of the canines and molars, the side between the tooth and the cheek. This is where most of the plaque and tartar accumulate. It may take several days to work up to brushing all of the teeth. It is not as critical to brush the tips or insides of the teeth if your dog will not cooperate. Most plaque and tartar accumulate on the outer surfaces of the teeth, so this is where you should direct your efforts, according to Dr. Bellows. The plaque that forms on the inner surface of the teeth tends to be removed by the dog’s tongue, reducing the need to brush on the inside.

Gradually work up to cleaning the teeth for 30 seconds on each side of the mouth.

Dog toothbrushes suitable for Havanese include those with angled handles, small brushes that fit comfortably in your hand, and finger toothbrushes (designed to fit over the tip of your finger). You can also use a very soft toothbrush made for human babies. The best toothbrush for your dog depends to a certain degree on your own dexterity. When just beginning the toothbrushing routine, some pet owners prefer the finger toothbrush. If you are uncertain of which brush to use, check with your veterinarian.

Plaque and tartar should not be removed at home with a human dental scaler. Dr. Bellows states that some of the visible tartar above the gum line can be removed with a scaler, but the plaque and tartar below the gum line will continue to cause periodontal problems. In addition, it isn’t possible to scale the inner surfaces of the teeth in a conscious dog, and the scaler will cause microscopic damage to the tooth surface, ultimately damaging the tooth.

For preventative home care, Dr. Bellows states:” There are hundreds, if not thousands, of dental products in the pet stores that make claims that, unfortunately, are not substantiated. Often, claims for whiter teeth, cleaner breath, controls gingivitis, do not have the research behind them.” A complete list of products that are scientifically proven to reduce plaque and tartar is published by the Veterinary Oral Health Council (VOHC), an organization of veterinary dentists and dental scientists appointed by the American Veterinary Dental College. These products include dental diets, edible chew treats, water additives, oral gel spray, toothpaste, toothbrushes and wipes. The VOHC certifies that these products provide at least a 20% reduction of plaque and tartar in dogs. A link to the VOHC list is included in the resources section of this article.

TREATMENTS

Cleaning

Once your Havanese has severe tartar accumulation a dental cleaning under anesthesia is the only way to get back to a clean slate. The build-up of tartar will not be able to be removed by a toothbrush, treats or additives.

Dental cleanings are performed under general anesthesia, as this is the only way to thoroughly clean below the gum line. There are risks with general anesthesia, but measures can be taken to keep the risks low. Pre-operative bloodwork is an important step that should not be skipped. These tests provide details about how well the liver and kidneys are functioning, how well the red blood cells carry oxygen to the tissues, and how effectively the white blood cells can fight infection and respond to inflammation.

Your dog’s dental typically consists of probing around the teeth for gum line pockets where food can accumulate and decay, cleaning the teeth with a hand and an ultrasound scaler and polishing to leave a smooth surface which deters plaque adherence. Since it can be difficult to predict the extent of dental disease before the teeth and gums have been checked, you may be contacted after the procedure has begun to discuss additional required treatment. It is not unusual for an antibiotic to be required for a period after the cleaning, especially if teeth have been extracted.

Cleaning Without Anesthesia

Many dog owners consider non-anesthetic dental cleanings, but these are not recommended by Dr. Wong. Non-anesthetic dental cleanings only clean above the gum line. It is the tartar below the gum line that causes the most significant periodontal disease. Furthermore, no polishing is performed, leaving a rough tooth surface that will attract subsequent plaque build-up.

RESOURCES:

For more comprehensive information on dental health issues and treatment click on the following link:

American Veterinary Dental College: https//www.avdc.org/

To find a board-certified dental specialist in your area click on the following link:

http://www.avdc-dms.org/dms/list/diplomates-map.cfm

Veterinary Oral Health Council. (2021) VOHC® Accepted Products for Dogs

Retrieved from http://www.vohc.org/VOHCAcceptedProductsTable_Dogs.pdf

REFERENCES

- AKC Canine Health Foundation. (2012) Canine Dental Health Care. Retrieved from https://www.akcchf.org/educational-resources/library/articles/dental-health-for-dogs.html

- Hiscox, Lorraine, DVM FAVD Dip. AVDC; Bellows, Jan, DVM, Dipl. AVDC, ABVP. (n.d.) Persistent Deciduous Teeth (Baby Teeth) in Dogs. Retrieved from https://vcahospitals.com/know-your-pet/retained-deciduous-teeth-baby-teeth-in-dogs

- Chihuahua Club of America (2008) Oral Disease Considered Common Problem in Chihuahuas. Retrieved from http://www.chihuahuaclubofamerica.org/images/purina-pdfs/Purina-Oral-Disease.pd

- Bellows, Jan. DVM, Dipl. AVDC, ABVP. (2014). Periodontal Disease and Dental Health in Dogs (podcast, PDF file). https://www.akcchf.org/educational-resources/podcasts/podcast-transcripts/Periodontal-Disease-and-Dental-Health-Dr-Jan-Bellows.pdf

- Bellows, Jan. DVM, Dipl. AVDC, ABVP. (n.d.) Dental Cleaning in Dogs. Retrieved from https://vcahospitals.com/know-your-pet/dental-cleaning-in-dogs

- Williams, Krista BSc, DVM, CCRP; Ruotsalo, Kristiina, DVSc, Dip ACVP; & Tant, Margo S, DVM, DVSc. (n.d.) Pre-surgical Preparation and Testing. Retrieved from https://vcahospitals.com/know-your-pet/presurgical-preparation-and-testing

- Anastasio, Alexandra. (2021) Dog Anesthesia: What Every Dog Owner Should Know. Retrieved from https://www.akc.org/expert-advice/health/what-to-know-about-anesthesia/

V. Canine Cognitive Dysfunction

Authors: Kim Gillette, Esq. and Dr. Rafe H. Schindler

Introduction

Canine cognitive dysfunction, or CCD is a combination of what we know as Alzheimer’s Disease and dementia. The American Heritage Dictionary[1] defines these as follows:

- dementia (di’ men’ she) n. 1. Irreversible deterioration of intellectual faculties with accompanying emotional disturbance resulting from organic brain disorder. Madness, insanity.

- Alzheimer’s disease is (akts’ hi-merz, alts’) n. A severe neurological disorder marked by progressive dementia and cerebral cortical atrophy.

CCD, sometimes called “doggy dementia” is an age-related neurobehavioral syndrome in dogs that leads to a decline in cognitive function. It is a unique disorder that is not breed specific, but rather age dependent. It affects all dog breeds equally. The prevalence of CCD in smaller breeds, such as Havanese, arises only because these breeds tend to live longer, and the dog’s owners are able to observe more of the symptoms emerging over time.

Manifestations of CCD:

CCD is an umbrella term embracing four separate cognitive behavioral patterns:

1. Involutive depression: This occurs in the dog’s later years and is similar to chronic depression in humans. Untreated anxieties seem to play a key role. Some of the symptoms include circling, wandering, house soiling, lethargy, sleep disorders, decreased learning and vocalizing.

2. Dysthymia: This causes a loss of awareness of body length and size. Dogs with dysthymia often get stuck behind furniture, or in a corner. Other common symptoms of dysthymia are disrupted sleep-wake cycles, constant growling, whining or moaning, and aggressive behavior.

3. Hyper-Aggression: Dogs with hyper-aggression tend to bite first and warn second.

4. Confusional syndrome: This is the profound decline in cognitive ability. It is the closest thing to Alzheimer’s in humans. Confusional syndrome results in a decrease in activity levels. A decreased desire to explore and a decreased response to things, people and sounds in the dog’s environment. The dog is less focused and shows altered responses to stimuli. With confusional syndrome, dogs forget familiar features in their lives and in more advanced stages, dogs forget who their owners are.

Distinguishing CCD from Other Physiological Causes

The changes associated with CCD are subtle, and the gradual variations in the dog’s behavior can be challenging to notice for even the most attentive owner. In her book, “Remember Me? Loving and caring for a dog with Canine Cognitive Dysfunction”,[2] Eileen Anderson lists the most frequent signs of CCD:

- Pacing back and forth or in circles.

- Staring into space or at walls.

- Walking into corners or other tight places and staying there. Lack of spatial awareness.

- Appearing lost or confused in otherwise familiar places.

- Waiting at the hinged side of the door to go out.

- Failing to get out of the way when someone opens a door.

- Failing to remember routines or starting them and getting only partially through.

- Sundowning or mixing up wake and sleep patterns. A change in sleep patterns or a disruption in circadian rhythms is one of the more specific symptoms related to canine cognitive dysfunction. A dog that used to sleep soundly at night, now paces all night long.

- Altered interactions with family members or other pets. Social behavior replaced with crankiness and irritability.

- House soiling. This is one of the most common ways CCD is distinguished in dogs, especially if the dog was previously house trained.

- Changes in activity level.

Taken together these are the most common signs of CCD, however individually they may simply be a serious medical problem and not CCD. A thorough physical exam including blood pressure measurement, urinalysis, blood tests, and a careful review of the medical history should be used to rule out health problems that have similar symptoms to CCD. Some examples follow.

The behaviors associated with the onset of impaired vision and/or loss of hearing in older dogs can frequently be confused with CCD. Loss of hearing and/or site can lead to confusion and less interaction with family members, but not be CCD.

Health issues in senior dogs such as diabetes, millitus, Cushing’s disease, kidney disease and incontinence, can all lead to unexpected urination in the house, yet have nothing to do with CCD.

Hyperadrenocorticism (HAC, or Cushing's disease) is a common cause of dysthymia-like symptoms which are unrelated to the progression of CCD. Rather, it is a common endocrine syndrome that happens to affect middle-aged and older dogs. HAC is generally caused by tumors of either the pituitary or adrenal glands[3] and is sometimes the result of long-term steroid therapy.

These examples show that when standard tests reveal no physiological cause for the CCD symptoms, it is time to consider CCD as the root cause.

Physiological Causes of CCD

The underlying cause(s) of CCD are not fully understood, but its onset is always associated with the development of accumulations of sticky proteins called “beta-amyloid plaques” around neurons, and the breakdown of the neurons themselves, resulting in so-called neurofibrillary tangles. These plaques and tangles are seen to inhibit the normal functioning of the inter-cellular communication required by the nervous system. In the body, nerve cells fire nerve impulses to release neurotransmitters, which are just chemicals that carry signals to other cells (including other nerve cells). These relay their message by traveling between cells and attaching to receptors on target cells. Some of the most familiar transmitters are serotonin, dopamine, acetylcholine, endorphins, and epinephrine. These are actually just a few of more than one hundred that have been identified and associated with control of one or more specific functions.

Each neurotransmitter attaches to a unique receptor — for example, dopamine molecules attach to dopamine receptors. Upon attachment, they trigger a specific action in the target cells. There are (1) excitatory neurotransmitters which encourage a target cell to take action, (2) inhibitory neurotransmitters which decrease the chances of the target cell taking action, and (3) modulatory ones which signal many neurons at the same time, as well as communicate with other neurotransmitters. After completing their function neurotransmitters are either broken down or recycled by the body.

The brain in particular uses neurotransmitters to regulate many necessary functions, including heart rate, breathing, sleep cycles, appetite, digestion, mood, concentration, and muscle movement. One can therefore see that the interference in neural communication caused by plaques and tangles can change the normal functions into the ones we likely associate with CCD.

As a simple example, Serotonin has a profound affect over emotions and regulates mood, enhances a positive feeling and inhibits aggressive response, while Dopamine helps to focus attention and promotes feelings of satisfaction. A lack of these two neurotransmitters can cause irritability, limited impulse control, over reactivity including hyper - aggression, anxiety, and greater sensitivity to pain.

The similarity of CCD to Alzheimer’s in humans is therefore not a coincidence, as the manner in which the brain changes in the two conditions is found to be very similar. Both humans with Alzheimer’s and dogs with CCD both get the beta-amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles which block the normal communication between neurons by the neurotransmitters.[4] In both human and canine brains, beta-amyloid plaques are commonly detected both in extracellular space as senile plaques and also around the blood vessels.[5] While the neurotransmitter chemicals are themselves identical in dogs and humans, their detailed impact on behavior (such as the way emotions are processed) may differ between the species simply because of differences in the geometry of their brains.

Nevertheless, the result is that dogs exhibit impairment in many mental processes that directly parallel human symptoms, such as disorientation, memory loss, changes in behavior, and changes in mood, which can include hyper-aggression, and these are all tied to degradation in the performance of their common neurotransmitters.

Treatment of CCD:

CCD is currently considered irreversible -- there is no cure for CCD. However, some of the four separate cognitive manifestations of CCD may be preventable, and some symptoms can be minimized.

The drug that is primarily used to treat CCD by improving brain functions is selegiline (Anipryl). It is a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI), thought to improve brain chemistry by reducing the breakdown of dopamine and other neurotransmitters.

Other drug treatments include Nicergoline, which is prescribed in the UK and Propentofylline, used in some European countries and in Australia. The former enhances blood flow to the brain and is thought to enhance the transmissions of neurons. The latter drug is thought to increase blood flow by making the red blood cells more pliable and preventing them from clumping together. Propentofylline is sold as the veterinary medicine Vivitonin.[6]

A vet can recommend other medications that will make senior dogs less anxious and sleep better. Therapeutic dog foods that support cognitive functions may be utilized. It is best to give senior dogs exercise, keeping him/her as active as possible. Finally, a vet can prescribe medications that help minimize the other symptoms of CCD.[7]

Caring For Dogs Diagnosed with CCD

Dogs with CCD need special precautions taken with them. Always make sure they have proper identification on them. The changes in their sleep and awake cycles can result in them wandering away and getting lost. Avoid leaving a dog with CCD alone. Remember the aging process is just as scary for the dog as it is for the owner. If soiling inside the house becomes an issue, a dog’s access to areas can be limited inside by using gates and potty pads, or utilizing doggy diapers or belly bands. Senior dogs should be taken out more often and not scolded for having accidents.

Summary and Prognosis

As dogs are living longer nowadays, there are many more cases of CCD being seen. Indeed, by the time a dog reaches ~14 years of age, he/she has a 40% chance of developing CCD. Overall, the disease affects up to 60% of dogs older than ~11 years.[8] As noted earlier, the prevalence of CCD does not differ between breeds[9] and there are no breed specific differences in clinical signs or pathology of the disease. However, as larger breeds typically have shorter lifespans than smaller ones[10] clinical signs of CCD are more often observed and reported in smaller dogs.[11], [12]

Interestingly, the life expectancy of senior dogs is not impacted by the presence of CCD10. Dogs with CCD live normal life spans, and indeed, the referenced study showed the group with CCD had slightly longer lifespans. Researchers speculate that this could be a result of the higher quality of medical care that these dogs got due to their underlying condition.[13]

As indicated, several drugs are available which potentially reduce the progression of the disease and can also address some of the symptoms. Unfortunately, there are no biological markers that would allow accurate and early diagnosis of CCD in dogs. In most cases, the assessment of cognitive functions through neuropsychological tests and by exclusion of other physiological conditions with overlapping symptoms is sufficient to confirm the diagnosis when the disease has progressed, but markers for detecting CCD in its early stages would be very useful in veterinary medicine.[14]

[1] American Heritage Dictionary, Second College Edition, published by Houghton Mifflin Company. (1982)

[2] Eileen Anderson, Remember Me? Loving and caring for a dog with Canine Cognitive Dysfunction, 1st Edition, ISBN 978-1-943634-00-2. Published by Bright Friends Productions (2015).

[3] Overview of Hyperadrenocorticism, by Cindy Cohan, VMD, published by VetFolio/Veterinary Technician.

[4] Cummings BJ, Head E, Afagh AJ, Milgram NW, Cotman CW. Beta-amyloid accumulation correlates with cognitive dysfunction in the aged canine. Neurobiol. Learn Mem. 1996 Jul;66(1):11-23. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1996.0039. PMID: 8661247.

[5] Sonja Prpar Mihevc and Gregor Majdič, Canine Cognitive Dysfunction and Alzheimer's Disease - Two Facets of the Same Disease? Front Neurosci. 2019 Jun 12;13:604. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00604. PMID: 31249505; PMCID: PMC6582309.

[6] Siwak CT, Gruet P, Woehrlé F, Muggenburg BA, Murphey HL, Milgram NW. Comparison of the effects of adrafinil, propentofylline, and nicergoline on behavior in aged dogs. Am J Vet Res. 2000 Nov;61(11):1410-4. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2000.61.1410. PMID: 11108188.

[7]Doggie dementia is becoming more common now our best friends are living longer. Published in ABC Science by Nadyat El Gaveley, September 11, 2019.

[8] Fast, R., Schutt, T., Toft, N., Moller, A., and Berendt, M. (2013). An observational study with long-term follow-up of Canine Cognitive Dysfunction. Clinic characteristics, survival, and risk factors. J. Vet IM, 27(4), 822-829.

[9] Salvin H. E., McGreevy P. D., Sachdev P. S., Valenzuela M. J. (2010). Under diagnosis of canine cognitive dysfunction: a cross-sectional survey of older companion dogs. Vet. J. 184 277–281. 10.1016/j.tvjl.2009.11.007.

[10]Greer K. A., Canterberry S. C., Murphy K. E. (2007). Statistical analysis regarding the effects of height and weight on life span of the domestic dog. Res. Vet. Sci. 82 208–214. 10.1016/j.rvsc.2006.06.005.

[11]Vite C. H., Head E. (2014). Aging in the canine and feline brain. Vet. Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract. 44 1113–1129. 10.1016/j.cvsm.2014.07.008.

[12] Schmidt F., Boltze J., Jäger C., Hofmann S., Willems N., Seeger J., et al. (2015). Detection and Quantification of β-Amyloid, Pyroglutamyl Aβ, and Tau in Aged Canines. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 74 912–923. 10.1097/NEN.0000000000000230

[13] See Reference 2.

[14] See Reference 5.